|

Date: 5th August 2008 | Venue: Courtyard

Theatre |

Tennant's performance, in short, emerges from a detailed framework. And there is a tremendous shock in seeing

how the lean, dark-suited figure of the opening scene dissolves into grief the second he is left alone: instead of rattling

off "O that this too too sullied flesh would melt", Tennant gives the impression that the words have to be wrung from his

prostrate frame. Paradoxically, his Hamlet is quickened back to life only by the Ghost; and the overwhelming impression is

of a man who, in putting on an "antic disposition", reveals his true, nervously excitable, mercurial self. This is a Hamlet of quicksilver intelligence, mimetic vigour and wild humour: one of the funniest I've ever

seen. He parodies everyone he talks to, from the prattling Polonius to the verbally ornate Osric. After the play scene, he

careers around the court sporting a crown at a tipsy angle. Yet, under the mad capriciousness, Tennant implies a filial rage

and impetuous danger: the first half ends with Tennant poised with a dagger over the praying Claudius, crying: "And now I'll

do it." Newcomers to the play might well believe he will. Tennant is an active, athletic, immensely engaging Hamlet. If there is any quality I miss, it is the character's

philosophical nature, and here he is not helped by the production. Following the First Quarto, Doran places "To be or not

to be" before rather than after the arrival of the players: perfectly logical, except that there is something magnificently

wayward about the Folio sequence in which Hamlet, having decided to test Claudius's guilt, launches into an unexpected meditation

on human existence. Unforgivably, Doran also cuts the lines where Hamlet says to Horatio, "Since no man knows of aught he leaves,

what is't to leave betimes? Let be." Thus Tennant loses some of the most beautiful lines in all literature about acceptance

of one's fate. But this is an exciting performance that in no way overshadows those around it. Stewart's Claudius is a supremely

composed, calculating killer: at the end of the play scene, instead of indulging in the usual hysterical panic, he simply

strides over to Hamlet and pityingly shakes his head as if to say "you've blown it now". Oliver Ford Davies's brilliant Polonius

is both a sycophantic politician and a comic pedant who feels the need to define and qualify every word he says: a quality

he, oddly enough, shares with Hamlet. And I can scarcely remember a better Ophelia than that of Mariah Gale, whose mad-scenes

carry a potent sense of danger, and whose skin is as badly scarred by the flowers she has gathered, as her divided mind is

by emotional turmoil. That is typical of a production that bursts with inventive detail. I love the idea that Edward Bennett's Laertes,

having lectured Ophelia about her chastity, is shown to have a packet of condoms in his luggage. And the sense that this is

a play about, among much else, ruptured families is confirmed when Stewart as the Ghost of Hamlet's father seeks, in the closet

scene, tenderly to console Penny Downie's plausibly desolate Gertrude. Audiences may flock to this production to see the transmogrification of Dr Who into a wild and witty Hamlet.

What they will discover is a rich realisation of the greatest of poetic tragedies. Date: 5th August 2008 | Venue: Courtyard

Theatre |

David Tennant, known to millions as BBC TV's Doctor Who, has returned to his thespian roots as the lead in

Hamlet.

The Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) production, staged in Stratford-upon-Avon, takes a modern-day approach to the great

Shakespearean tragedy.

It also stars Star Trek actor Patrick Stewart as Claudius, Peter de Jersey as Horatio, Mariah Gale as Ophelia and Pennie

Downie as Gertrude.

The production is helmed by RSC chief

associate director Gregory Doran.

From the second David Tennant made his entrance as Hamlet in the RSC's latest production, it was clear just who was the

star of the show.

Unannounced, almost anonymously, he walked silently to the corner of the stage, and stood forlornly, his hand clasped around

a champagne-glass.

But all eyes at the Courtyard Theatre immediately sought out the lanky Scotsman who has endeared himself to millions as

the 10th Doctor Who on the cult TV series.

And he was not there to disappoint. He seized the role of the young man haunted by his father's ghost with both hands and

ran with it. Literally.

Boyish energy

At first he is reserved. His hair is swept back and as stiff as his demeanour as his uncle Claudius marries his mother,

Gertrude. Standing under the crystal chandeliers he is seemingly oblivious to the celebrations around him.

But when he crouches to the floor, alone, and gripped by unbearable despair, his grief and rage overwhelm.

And it's not long before Tennant's more familiar, frenetic acting comes to the fore.

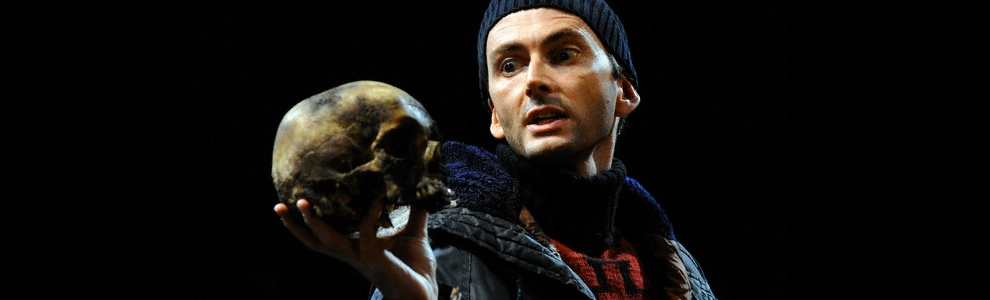

In an early scene where he encounters his father's ghost, some of his expressions - the bulging-eyed fear, the bared teeth

and furrowed brow - are reminiscent of the Doctor.

He races about the stage with ease - all lanky limbs and boyish energy - switching seamlessly between sanity, feigned madness

and humour.

In many of the scenes Tennant is barefoot, which adds to the intimacy of the play. The costumes too are pared-down and

modern.

It is, perhaps, the first time Hamlet has worn a Parka jacket and beanie hat. Tennant carries it off with quirky aplomb.

Tennant also uses his hair to great theatrical effect. From the sleek combed-back style of his first scene, he ruffles

it to display despair, rage and madness. It deserves a credit of its very own.

Overall, his performance is undoubtedly mesmerising. What he lacks in emotional intensity, he makes up for with wit, humour

and stirring energy.

Tennant is at his best, though, when he allow his full dramatic force to take over. The scene in Gertrude's bedroom when

he challenges her on her "incestuous" bed is menacingly powerful.

And he delivers the play's most famous lines without fanfare. They are there, subtle and seamless.

Stewart, too, deserves credit for his understated scary portrayal of Claudius. He is the chilling calm to Tennant's vivacity.

Peter de Jersey's Horatio is wonderfully endearing, Oliver Ford Davies is hilarious as doddery old Polonius, while Mariah

Gale's Ophelia has a haunting vulnerability.

But all eyes will undoubtedly remain on Tennant as he continues his run as the Prince of Denmark. It has, perhaps inevitably,

become known as the Doctor Who Hamlet.

And while Tennant may not be the best Hamlet the RSC has ever produced, he could soon be a serious challenger for the crown.

When David Tennant plays Doctor Who he relies on one expression. His eyes become bulging marbles, his teeth turn into big

white tombstones and his forehead slightly puckers, giving the impression that he hopes to repulse uppity Daleks and other

outer-space jetsam with no more than aghast looks, incisors and a wrinkle. But Gregory Doran’s fluent, pacey, modern-dress

revival of Hamlet gives Tennant the chance to show the world that he has the range to tackle the most demanding classical

role of all – and, praise be, he seizes it. I’ve seen bolder Hamlets and more moving Hamlets, but few who kept me so riveted throughout. Even when Tennant boggles

in wonder at his father’s ghost or dismay at his incestuous mother, his eyes, teeth and steep, furrowed brow don’t

do all the acting. Indeed, the first surprise is the intensity of his mourning. He stands there in his black suit and tie,

impervious to the champagne drinkers partying beneath their crystal chandeliers, and then, left alone, he twists, half-collapses,

crouches, squeals and screeches in an agony of grief, rage and disgust. And then comes the second, concomitant surprise. We’ve already met Patrick Stewart’s Claudius, a smiling, slippery King who exudes a geniality that, thanks

to his sly glances and evident distaste for Hamlet, we know to be spurious. And now we meet his dead brother, who is also

Patrick Stewart, but a very different Patrick Stewart. This scarily corporeal ghost circles Tennant’s Hamlet, who has

sunk to his knees, and roars out his demands like some monstrous dictator or aggrieved ogre. Even after he’s grimly

exited the stage he dominates it, turning his cries of “remember me” and “swear” into ferocious orders,

the latter making the theatre quake and shake as much as his former subjects. This leaves you wondering if Hamlet’s father really was a more appealing ruler than his usurping brother. More importantly,

it gives added urgency to the oldest Hamlet question of all. Why does the Prince delay the revenge that he has promised this paternal powerhouse? That’s something to exercise

the amateur shrinks in the audience, who will note that Tennant’s Hamlet ends the closet scene by burying his head in

the lap of Penny Downie’s baffled, stricken Gertrude, then gives her a needy, imploring look and kisses her on the lips.

Yet, praise again be, Tennant isn’t the sort of reductively Oedipal Hamlet who should ideally be stretched out on Dr

Freud’s sofa bed. Nor is he one of those Hamlets who, while faking mad, actually becomes mad or half-mad. True, he skims

about the black, shiny stage in jeans and bare feet, alarming the court; but that’s a sane man’s calculated diversion.

If there’s a nonpsychiatric explanation for his inaction it’s maybe a more traditional addiction to “the

pale cast of thought”. Tennant is restless, curt and mocking when he needs to be, affectionate when he can be, and, apart from an occasional tendency

to gabble, pretty impressive. But most noticably he’s so dreamily reflective that you feel that Claudius’s fatal

mistake was refusing him permission to resume his philosophy degree in the safety of faraway Wittenberg. Like Gordon Brown,

who came to a preview, this very temporary leader is error-prone. Doran isn’t a director who goes in for gratuitous oddities, but there are one or two in his production. I liked the

transformation of the dumb show that precedes the play-within-the-play into a piece of subversive burlesque, with the Queen

played by a blubbery, whooping pantomime dame, but I hated the cut that means we get no explanation of Hamlet’s failure

to reach England and no mention of his morally questionable destruction of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. Almost as bad, Fortinbras makes a final appearance as an SAS general flown in from Norway, but remains weirdly mute, saying

nothing about Hamlet or anything else. However, there can be no complaint about the supporting performances, least of all

Oliver Ford Davies’s Polonius. Not that the overall woes of the Polonius family are handled with total success. Mariah Gale, a pleasant, obedient young

women who wears pedal pushers, doesn’t seem much in love with Hamlet. Nor does she display the feelings for her father

that would explain her madness after Hamlet has, in this updated Elsinore, shot him dead. But Polonius himself is another

matter. That old politician is usually either canny and tough or he’s an amiably potty family man. Ford Davies solves

the dilemma this presents by being both, now intently eyeballing and lecturing Gale’s Ophelia, now drifting off into

a senior moment. With him in top form, Stewart demonstrating his versatility, and Tennant definitively quitting his Tardis,

this is a revival to relish.

He's alienated, adrift in an inimical universe, and subject to bouts of existential depression and to fits of larky lunacy.

He gives the impression of knowing more than he can possibly tell to other creatures. From time to time, he exhibits a penchant

for sporting student scarves and he exudes the air of a brilliantly batty, eternal undergraduate. Yes, it's clear that Doctor

Who must have been a key role model for young Hamlet. Perhaps the Tardis touched down in Elsinore during the troubled Dane's

formative years. You don't, though, need to resort to such desperately strained analogies in order to justify the casting of David Tennant

as Shakespeare's most complex hero. Another doctor, Jonathan Miller, recently attacked the English theatre's "obsession with

celebrity" – dismissing Tennant as "the man from Doctor Who" and castigating producers for their attachment to the "merely

famous". It's an odd charge coming from a man who gave Joanna Lumley (not exactly media land's best kept secret) the leading

part in his Sheffield revival last year of The Cherry Orchard. Some of Miller's points are valid. Hollywood stars with scant stage experience are good only for box office (and not always

for that). But he's way off the mark with Tennant, who is classically trained, with two earlier seasons at the RSC under his

belt and the veteran of a number of roles that are sterling preparation for Hamlet, including a wittily edgy Romeo and a manically

mordant Jimmy Porter, that latter-day Angry Young Man. Besides, it's pure snobbery to suppose that Doctor Who fans and people who can appreciate Hamlet are mutually exclusive

groups. This is proved by the audiences for Greg Doran's powerful modern-dress revival in which Tennant turns in an extremely

captivating performance. It's a joy to see Stratford's vast Courtyard Theatre packed to the rafters and liberally sprinkled

with children who remain rapt throughout. And the focusing effect of a booked-out house is intensified because of the huge

wall of mirrored panels at the back of the long thrust stage. This reflects the audience and the chandeliered palace and allows

for vivid special effects. In the closet scene, Hamlet shoots the eavesdropping Polonius with a revolver and the glass crazes

into a huge, psychologically suggestive spider's web of cracks. The production has plenty to offer Shakespeare aficionados and young first-timers, even if certain broad touches feel faintly

gratuitous – such as taking the interval on an artificial cliffhanger with Hamlet's flick-knife suspended over Patrick

Stewart's praying Claudius. Tennant is adept at most aspects of the role but he excels when the prince becomes a prankish provocateur. A lanky live

wire with a wry twist to the mouth and mocking brows, he puts on a thrillingly risky display of barbed levity and flippant

sarcasm. Even when strapped to a swivel office chair by Claudius's henchmen, this Hamlet manages to improvise a subversive

joke that insults his uncle. He whizzes away to his enforced exile on its castors with the sardonically exuberant cry of "Come,

for England, wheeeee!!". Barefoot in a DJ, he can hardly contain his baleful delight before the play-within-the-play and,

in its chaotic aftermath, he slouches over the throne, his suspicions triumphantly confirmed, mangling "Three Blind Mice"

on a recorder and with the crown resting on his head at a rakish angle. Tennant gives a further serrated edge to this confrontational comedy through the variety of voices he deploys. There's

the spoof bored sing-song for the politically incendiary quibble: "The body is with the king, but the king is not with the

body. The king is a thing –" or a doddery, toothless old man delivery when he twits Polonius with the idea that there's

nothing he would more willingly part with than Polonius's company "except my life, except my life, except my life". This side of his portrayal is of a piece with a production that finds many opportunities for queasy black humour. Mariah

Gale's haunting Ophelia, nobody's fool at the start, seems unsurprised to fish out contraceptives from her brother's suitcase.

Polonius's sheer purblind irresponsibility as a father is hilariously and horridly emphasised in Oliver Ford Davies's superb

performance by his habit of drifting off into donnishly absent-minded world of his own – especially when making crucial

and intrusive decisions about his children. The grimmest gag of all comes in the final hectic scene of slaughter. This Hamlet

doesn't need to force the poisoned wine down the throat of Patrick Stewart's creepily self-possessed Claudius. Handed the

goblet, Stewart raises it in a cynical salute to his troublesome nephew before downing its contents. It's diabolical cheek:

a gesture of "good health" to a man who has only minutes to live because of the drinker's own machinations. I rate Tennant very highly, but I wouldn't put him in the absolute front rank of contemporary Hamlets, a category which,

for me, includes Simon Russell Beale, Mark Rylance and Stephen Dillane. Or not yet, at any rate. The performance has time

to grow. This actor has most of what it takes: the braininess, the breadth of spirit, the reckless irony, the bamboozling

banter, the sense of layered depth. He can produce moments of sudden stillness when he seems to be dazed by the vortex of

meditation. After ecstasies of anger in the closet scene, he can turn into a deeply affecting lost boy kneeling by Gertrude's

bedside and trying to reconnect the primal family circuit. But while this Prince is able to reach out and touch his father's

Ghost (Patrick Stewart, doubling), his mother can neither see nor feel him. So what's missing? Well, the part of Hamlet constitutes a special case. However hard you analyse his behaviour and motivations,

this character remains to some degree a tantalising mystery. He's not exactly a Rorschach blot – though a critic has

astutely pointed out that the idea of one is anticipated in the cloud that Hamlet forces Polonius to agree looks like a camel,

a weasel and a whale. But it's why the role is particularly revealing about the personality of the actor playing it. (You

don't have to be the poet Coleridge to think "I have a smack of Hamlet, myself, if I may say so".) In the soliloquies, the

finest performers seem to be, partly, laying bare their own souls to us, too and laying us bare to ourselves. At the moment,

that strange double-feeling of exposure and spiritual connection is not as strong here as one could wish here. There may be technical reasons for this. It's a pity, for example, that Tennant is using an RP accent rather that his natural

incisive Scots lilt that might promote greater intimacy of rapport. One remembers how Fiona Shaw's acting was liberated when

she started to speak in her native Irish tones. And then there are some distancing and questionable directorial decisions.

This is not an account of the tragedy that plays down the politics (Stewart's low-key, canny portrayal demonstrates that Claudius

is the subtlest mind in the play after Hamlet) but the production ends with the arrival of a burly Fortinbras who is left

standing mute in the doorway. By axeing Horatio's speech of explanation ("so shall you hear/Of carnal, bloody and unnatural

acts") which reduces the revolutionary drama we have seen to the dimensions of a standard gory revenge play, the production

unwisely relieves the audience of the exquisite pain of feeling that we know this hero, who has poured out his soul for us,

better than any of the survivors. I expect that by the time the production reaches London, these problems will have sorted themselves out. Meanwhile, this

is a stirring and impressive theatrical event. The RSC is not allowing Tennant to sign sci-fi memorabilia – so you can

leave your reproduction sonic screwdriver at home. You never know, though, this Hamlet may switch some Shakespeare buffs on

to Doctor Who.

By some extraordinary quirk in the space-time continuum, two of our most famous intergalactic travellers have

simultaneously landed on Planet Hamlet. Having seen off Davros and the Daleks, Doctor Who must now adopt the disguise of Denmark's sweet prince to

do battle with Captain Jean-Luc Picard of the starship Enterprise, who has metamorphosed into the evil King Claudius. I'm sorry to sound flippant, but this production has become universally known as the Doctor Who Hamlet, with

even the local fish and chip shop promising to "exterminate" its patrons' hunger. And its sold-out success was largely dependent on David Tennant's presence in the title role, though theatrical

connoisseurs will also know that Patrick Stewart has been enjoying a golden run of classical performances since he quit space

travel. Casting Tennant was a far from cynical ploy, however. He has already done the RSC some service, spending several

seasons with the company as an exceptionally promising young actor whose roles included Romeo. Nor should his performance as Doctor Who be mocked. Funny, clever and with sudden flashes of deep emotion,

Tennant's time lord strikes me as a pretty good jumping off point for the most famous and challenging of all Shakespearean

characters. So how does he fare? Well, Tennant isn't in the pantheon of the great Hamlets yet. As a student prince, who

swaps his formal suit of mourning for jeans and T-shirt in Gregory Doran's sometimes brutally cut production, he captures

the character's intelligence, wit and quicksilver mood changes. What's lacking, at present, is weight and depth. He delivers the great soliloquies with clarity, but he doesn't

always discover their freight of emotion. In "To be or not to be" for instance, you never, as you undoubtedly did in Ben Whishaw's

recent performance at the Old Vic, feel that this is a man wrestling with the possibility of suicide. The "nunnery" scene when he suddenly turns on Ophelia lacks the required intensity and savagery, and at the

end you don't feel that this is a Hamlet who has achieved a sense of spiritual illumination. Tennant's prince seems merely resigned and wearily fatalistic, a reductive reading of a role that can offer

a moving glimpse of grace, as the Christian imagery of the last act suggests. There remains much to admire. It's hard not to warm to a Hamlet who makes you laugh, and Tennant discovers

almost every ounce of sarky humour, especially when baiting Oliver Ford Davies's hilariously ponderous but poisonous Polonius

and winding up the smarmy Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. Tennant is at his best though when he dares with his emotions and lets rip. The closet scene with Gertrude,

when he confronts his mother with her moral laxity, standing astride her on the "incestuous sheets" of her bed, has a thrilling

raw power. And there is a beautiful moment when the ghost of his father seems to hug him and Tennant delivers a little

gasp of love and grief. As the run continues, Tennant should trust his feelings, dig deeper, expose more of himself. I have no reservations at all about Stewart, who delivers the strongest, scariest performance as Claudius

I have seen. A modern tyrant in a surveillance state full of spies, informers and two-way mirrors in Doran's thriller-like

production, he presents a fašade of smiling, bespectacled geniality. It's so persuasive that it is easy to forget that he has murdered his brother to assume power. Yet there are

sudden glimpses of steely danger - a moment when he creeps up on Gertrude for instance and you are not sure whether he is

going to embrace or throttle her. But Stewart also suggests a man terribly burdened with a guilt he knows he can never expunge and you almost

feel sorry for the bastard. This is acting of the highest order with Stewart also doubling as a superb and terrifying Ghost.

Penny Downie harrowingly charts Gertrude's decline from high society lady to abject terror and exhausted,

alcoholic remorse; Mariah Gale makes a deeply poignant Ophelia; while as Laertes, Edward Bennett transforms himself with aplomb

from goofy Hooray Henry to fearsome assassin. With fine support from Peter de Jersey as a touching Horatio and a genuinely funny gravedigger from Mark Hadfield,

this is a gripping Hamlet that could become great if Tennant finds the courage to raise the dramatic stakes still further.

Date: 5th August 2008 | Venue: Courtyard

Theatre |

Date: 5th August 2008 | Venue: Courtyard

Theatre |

Having sold out for its entire run until mid-November, with tickets being traded for crazy prices on eBay, this Hamlet

faced a tall order in living up to its anticipation as one of Royal Shakespeare Company’s biggest events for years. Remarkably, it very nearly succeeds. This is among the most gripping and compelling accounts of the play I have seen. The main reason is that it has a simply electrifying performance from David Tennant in the title role, but this is an outstanding

solo performance at the heart of an outstanding ensemble production. And once again, the Courtyard itself, with its exciting relationship between actors and audience, is one of its stars.

That is apparent from the very first scene, where as the sentries fumble in the dark there is a feeling of being right there

with them on Elsinore’s battlements which I have never quite experienced before. There is no getting away from the fact that the title roles in Doctor Who and a Stratford Hamlet are

an extraordinary combination, but David Tennant is an actor with the ability to span the distance with what he makes look

like ease. It’s a freewheeling, some might feel self-indulgent performance of great physical energy which connects strongly

with the grim humour of the play. Tennant takes licence from the fact that Hamlet is himself playing a part, and I thought

at first he might be overdoing the mannerisms and funny voices, but his self-assurance is hard to resist. It’s as though

Shakespeare’s words are not so much being delivered as given a thorough work out: I’ve never heard the lewd insinuation

of “country matters” made quite so unmistakable. Gregory Doran’s production is lean and pacey. Some cuts include Hamlet’s tedious letter about his adventure

with the pirates, so it’s anyone’s guess where he’s coming from in the graveyard scene or what happens to

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. Six chandeliers are lowered to signify the Danish court and dress is modern, so that Tennant does “To be or not to

be...” in tee-shirt and jeans on a bare stage, daringly making it look like a rehearsal. The play-within-a-play, by

contrast, is given a lavish Elizabethan dressing. Patrick Stewart doubles the roles of Claudius and the Ghost, pointing up the contrast between Hamlet’s father and

his bespectacled, peacemaking brother, who has the air of a benign politician or a philanthropic businessman. It’s an

interesting and unusually sympathetic treatment of the character. Penny Downie is also a more than usually youthful and slinky Gertrude, and this is the first time I’ve heard Hamlet’s

squeamish, not to say politically-incorrect, reproach for his mother’s sexuality greeted with an ironic laugh. Other notable contributions include Oliver Ford Davies’s beautifully conceived Polonius, less querulous than is often

the case if no less pedantic, John Woodvine as a resonant Player King and Mark Hadfield, always to be relied on for a good

comic turn, as the Gravedigger. |

||||||

|

|

|

|

||||

|

David-Tennant.com is an independently owned fansite for the actor David

Tennant celebrating 11 years online in 2014.

|

||||||