|

HOW SHOULD we look back now on John Osborne's mould-breaking

Fifties drama, Look Back in Anger? With gratitude to non-iron shirts, which have relieved wives of the tedium of the thankless

task of ironing, and to women's lib for making it possible for men to steam ahead with the smoothing iron? With relief that

now, even in dreary Derby on a drab Sunday, there's something for people to do apart from ironing, drinking endless cups of

tea and dissing the predictable views of the Sunday papers? With disgust for a husband who so patronises his wife that he

wishes he could watch her experience the tragedy of losing a child in order to become "a recognisable human being"? However much attitudes may have changed in the half- century

since Osborne's voice raged - arousing cheers, controversy and contempt - his heavily autobiographical play is still gripping

in its awful intensity and sheer provocativeness. Played by a cast as good as that assembled by the Royal Lyceum, burgeoning

under the artistic direction of Mark Thompson, the details of Jimmy and Alison Porter's painfully edgy marriage hit home with

the precision of a marksman in Richard Baron's production. Cooped up in their dismal attic bedsit, like the animals

(bear and squirrel) into whose personalities they periodically escape, the Porters are brought brilliantly to hellish life

by David Tennant (soon to star in the new Harry Potter film) and Kelly Reilly, whose forthcoming appearances in four films,

alongside the likes of Dame Judi Dench and Audrey Tautou, have made her very hot property indeed. Tennant's rants may have

a coruscating effect on the audience, but Reilly's apparent indifference, her loud silence and her detached body-language

suggest another story. Is she numbed into passivity by his misogynistic bullying? Or exhausted by her claustrophobic existence,

cooped up with such a brittle bundle of seething energy and radical opinions? Tennant treats Trevor Coe's realistic set like a gym, working

out his frustrations as he jumps, perches and runs around in circles, his movements as feverish as his mind and as spiky as

his tongue. But there's a sensitive side to his portrayal, too - a touching vulnerability as he recounts his presence at two

deathbeds, and traces of the charismatic charm that make him irresistibly attractive. Reilly brings a hypnotic grace to the role of Alison, finding

her own passive path to survival in the jungle of their relationship, until the arrival of her friend Helena (Alexandra Moen),

representing the era of repertory theatre that Osborne's work changed irrevocably. She blows the whistle, summons Daddy (a

remarkably sympathetic Gareth Thomas), and crosses the floor in this game of sexual politics. There is good work, too, from Steven McNicoll as their

flatmate Cliff, who negotiates his way through the eruptions fizzing around him and, occasionally, sweeping him along, as

in the variety-style number into which Jimmy and Cliff seamlessly slip. The imagery and language have travelled surprisingly well

through time, even Jimmy's fascination with jazz trumpet, his pipe-smoking, his disillusion with stale politics, the fusty

establishment and rigid authority. But Baron also brings out the humour, tempering the incoherence of Jimmy's raging and the

bewildering placidity of Alison's unresponsiveness. The Britsh Theatre Guide Review |

Reviewed in Bath You can see how Look Back in Anger must have caused outrage

in its day, much as Joe Orton did ten years later. Even now, just short of a half century on - half a century! - one feels

a frisson run through the Bath Theatre Royal at some of the vicious barbs that Jimmy Porter, the original angry young man,

hurls at Alison, his long-suffering spouse, never more so than when he wishes that she, who, unbeknown to him is pregnant,

could have and lose a baby. It is genuinely shocking, the more so as Alison, first seen bent over

an ironing board like Picasso's blue guitar player, has offered no or little resistance. But Jimmy's behaviour is not meant

to seem gratuitous."One of us is mad," Jimmy, played by David Tennant, tells Alison, (Kelly Reilly). Either it's him, the

walking embodiment of The Scream, maddened by the hypocrisy, apathy and duplicity of those around him, or her, sunk in pusillanimous

torpor. The pain of losing a child he tells her is probably the only thing that will wake her up. Everything depends on the actor playing Jimmy, himself the embodiment

of the author. He has to convince us of Jimmy's menace and unappeasable rage, but he has also to remain in spite of this (and

partly because of this), fiercely lovable and attractive. It's a tall order for an actor to pull off. The mesmeric Michael

Sheen, most recently seen on stage in Caligula, realised it brilliantly a few years ago in a production which transferred

to the National Theatre. Here, David Tennant, most recently seen in The Pillowman, gives a fine performance, conveying

Jimmy's sense of pent-up frustration, bouncing off the walls of his attic Midlands flat, perching on and jumping off furniture. However, he lacks, perhaps because of his slight physical presence,

real menace and comes across as shrill rather than a latter-day Christ lashing the moneylenders from the temple. Perhaps too

Osborne's writing is to blame for my growing irritation with Jimmy's self-obsession. We learn that Jimmy watched his father

die when he was 10 and how his well-to-do mother and her relatives, eager for his father to spare them the embarrassment of

a protracted death, sparked an abiding class hatred and hatred of hypocrisy. But great as his grief is, does it excuse his indifference to the

suffering of others? I couldn't decide how far we are meant to sympathise with Jimmy who, it could be argued, is in a state

of retarded adolescence. The play's opening scene and Trevor Coe's cutaway dingy interior with rooftop, brilliantly conjure

up the dreariness of Sunday in the suburbs which I can remember, growing some years after the play premiered, only too well.

You understand Jimmy's sense of frustration at the drabness and dullness but his hostility is too omni-directional. It is

as if Osborne was so full of bile when writing the play he couldn't find the distance to give his material sufficient shape

and control Tennant is well supported, most notably by Steven McNicoll as Cliff,

Jimmy and Alison's slobbish but genial flatmate. Kelly Reilly, highly-praised in her recent West End outing in After Miss

Julie sparks fitfully but seems a little under-realised. Alexandra Moen as Helena and Garth Thomas as Colonel Redfern

make up the company with decent enough performances, particularly Moen who morphs effectively from aggrieved rectitude to

melting infatuation. The political, social and cultural landscape may have changed since

1956 but many of Jimmy's and thus Osborne's targets remain pertinent, namely, the smugness, hypocrisy and stifling conformity

of middle England. The wrath may be ultimately all-consuming and incoherent, but Jimmy's snarl to Alison that: "I want to

stand up in your tears and plash about and sing", reminds of a singular and singularly angry talent, worthily revived here

by director Richard Baron, still able to disturb and discomfit 50 years on. Rage on John Osborne! British Theatre Guide Review | Reviewed

in Edinburgh If the rest of this spring's shows at the Lyceum come anywhere close

to the quality of Look Back In Anger, Edinburgh theatre-goers are in for a stunning season. If not, at least the Lyceum

has started 2005 off with what may be the strongest production I've seen at this theatre since I arrived in Edinburgh in the

autumn of 2003. Look Back in Anger is the story of a married couple's

tempestuous relationship. Although it premiered in the late fifties the humanity of these characters is still completely accessible.

In this production, husband Jimmy Porter is played by David Tennant, with Kelly Reilly playing his wife Alison. Jimmy's pal

Cliff (Steven McNicoll) and Alison's school chum Helena (Alexandra Moen) are the opposing external forces that wreak havoc

on the Porters' marriage, and Gareth Thomas makes a brief appearance as Alison's father, Colonel Redfern. Without the crackling chemistry between all four of the younger cast

members, this could have been a very, very tedious play - one of those shows in which characters do a lot of standing around

shouting at one another. It's not that what they're saying isn't important or devastating - almost invariably Osborn's words

strike right to the heart of situations that are both heartbreaking and infuriating - but as happens in all the best productions

of well-written drama, what the actors bring to the story simply elevates the play to a whole new level of intensity. With the help of director Richard Baron, the company accomplishes

moment after moment of pure, fearless honesty. Whether this takes place in the form of Jimmy's impassioned ravings, Alison's

desperate silences, Cliff's unhesitating advocacy on behalf of the Porters, or Helena's calculated scheming, time and again

those involved with bringing this production to life are astonishing in their ability to expose the inner workings of these

characters. Osborn's characters are cruel and merciless with one another, tearing

one another's heads off one moment only to plead for understanding and love in the next. Audience members will see this demonstrated

over and over again from the early moments of the piece, and should realize what a rare privilege it is to witness such an

all-consuming display of talent from a group of such high calibre. Trevor Coe's set is complicated and gorgeous, and especially in the

first scene it makes use of colour in such a way that audience members discover each character unfolding from a dull background,

breathing their way into life as the show gets underway. The show runs until 12th February, and as Edinburgh is only a day's

train ride from any part of the UK, no theatre-lover in either Scotland or England has any excuse to miss seeing this sensational

production - until (as will happen if there's any justice in the world of theatre) the run sells out. First Night Review | The Times Online ONE of the many hopes for the nascent

National Theatre of Scotland is that it will strengthen casting. There are some fine actors resident in Scotland. But there are a lot more who have gone forth, from Ewan McGregor to

Denis Lawson, whom theatregoers, and perhaps equally importantly those who are not currently theatregoers, would love to see

on the stages of Scotland. So this production of John Osborne’s epoch-making

play, which brings David Tennant, lately of the BBC’s Blackpool but with a string of other television, film,

National Theatre and RSC credits, back home, could be seen as something of a preview. Happily, one’s immediate reaction is that if the new National

Theatre is going to do much better than this co- production between the Royal Lyceum in Edinburgh and the Theatre Royal in

Bath, it is going to have to go some.

Tennant is everything Jimmy Porter needs to be, odious but irresistible,

idle but driven, angry but powerless, selfimportant but self-loathing.

Endless energy leaks from every inch of his long, lean, angular frame

which he throws like a weapon around Monika Nisbet’s perfect recreation of the Porters’ shabby Midlands bedsit.

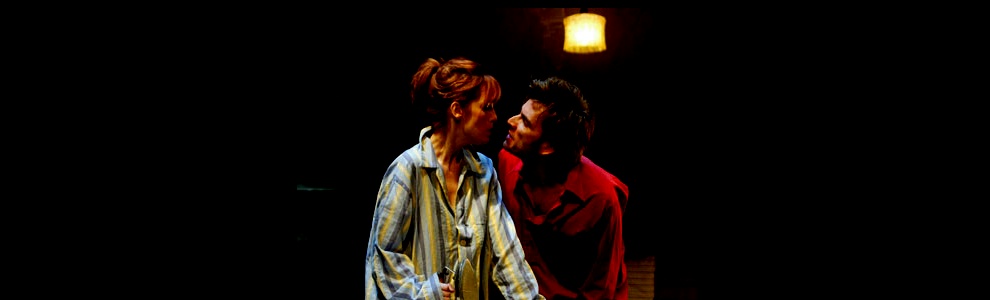

Tennant’s performance is matched in the other four parts. Alexandra

Moen is particularly fine as Helena, her disdain flipping over into lust.

After the first-act confrontation, their faces inches apart, when

she threatens to slap his face in defence of her friend Alison — Jimmy’s wife — and he threatens to slap

her right back, there is only one possible destination for their relationship. And, as Alison, Kelly Reilly’s final

speech, mourning the loss of her child, broke more than Jimmy’s heart on the first night.

Looking back through the prism of almost half a century at a play

which supposedly captured a moment in social history, it is, as many noted of the National Theatre revival five years ago,

the human drama rather than the class warfare which now resonates most.

Class has hardly disappeared from the lexicon of British life, of

course, nor can one imagine today’s shopping malls or old films on TV assuaging Jimmy’s Sunday afternoon ennui.

But it is that human drama which in Richard Baron’s expertly

constructed, naturalistic production makes such a good case for this being a play for all time, not just its own time.

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

||||

|

David-Tennant.com is an independently owned fansite for the actor David

Tennant celebrating 11 years online in 2014.

|

||||||